|

Propel Potential Model

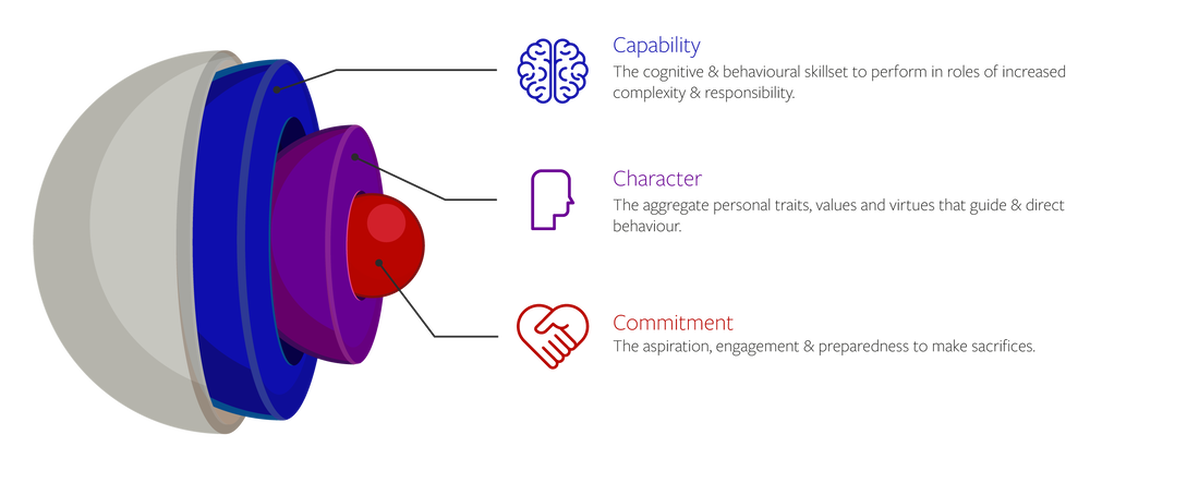

Capability | Character | Commitment One of the most important people-related questions businesses strive to answer is whether a talent has the potential to perform in the present and build for the future. Consequently, talent management teams within organisations place considerable effort and emphasis on getting the science of predicting potential right. This document outlines the philosophy and research underlying the Propel Potential Model. In addition, this review will explain the benefits of adopting a holistic assessment for potential that includes the three elements of Capability, Character and Commitment.

What is potential? As a starting point, it is important to create an equal understanding and dissect the term potential. Potential is typically defined as the culmination of an individual’s capability, motivation, characteristics and aspirations to advance in a more senior and strategic role (Silzer & Church, 2009). Interestingly, whilst these days half of organisations have a high-potential identification programme to appropriately identify and curate a leadership pipeline (Church & Rotolo, 2013), nearly 40% of internal moves made by ‘high potentials’ in an organisation end in failure (Martin & Schmidt, 2010). One reason for this is the lack of differentiation between high performers and high potentials. |

It has been well established that past performance is a valid predictor of future performance and therefore, an assessment process that solely considers past performance would indeed identify high performers.

Potential, on the other hand, is about what the individual can do in the future and predicting this purely based on past behaviours would neither be valid nor inclusive. As mentioned previously, the formula for measuring potential includes motivation, personal characteristics and aspirations, in addition to capability based on past performance. Why do we need to measure potential? According to Bauer (2011), half of all senior external hires in corporations fail within the first 18 months. This is primarily due to high emphasis on an individual’s past experience and the lack of a holistic multi-trait, multi-method assessment approach that looks not only at the end results an individual achieves themselves, but also ‘how’ they get things done. Measurement of potential demonstrates how different aspects of an individual come together to independently and collectively contribute to long-term success in a proposed role. Similarly, potential also considers the ability to adapt and strive in a particular company, whilst maintaining a certain level of learning agility, which has been shown to be a better predictor of high potential than even job performance (Dries, Vantilborgh & Pepermans, 2012). |

The Propel Potential Model

Integrating the findings of contemporary institutional and academic studies, as well as Propel’s own research into high potential across a wide range of organisations and industries, the Propel Potential Model organises the qualities that underpin potential into three distinct categories:

Capability

|

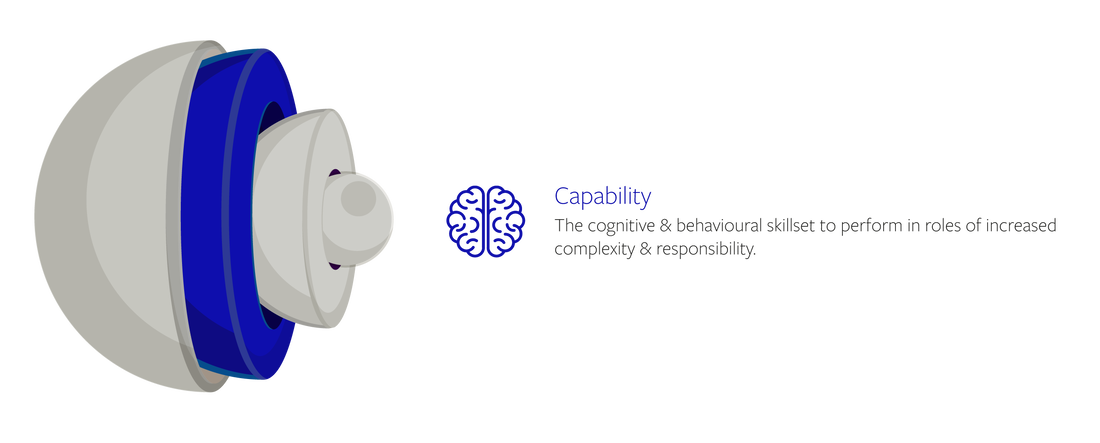

Capability consists of the cognitive ability and behavioural skillset to learn, develop and perform in roles of increased complexity and responsibility.

Competencies: The behaviours required for success that can be observed through performance or reliably predicted through psychometric. Competencies may be defined according to an organisation’s internal competency model or aligned to a research-based model such as the Propel Competency Framework* with coverage of the following domains:

Competency is further differentiated based on actual demonstrated capability (performance) and potential to demonstrate the required behaviours: |

Cognitive Ability: Intelligence or cognitive ability has long been demonstrated in research as the single-best predictor of job performance and in forecasting potential to excel in bigger, more complex jobs. Learning ability includes a substantial cognitive element allowing individuals to acquire new knowledge and skills fast in order to perform in roles of greater complexity (Schmidt, 2002). Assessing Capability: The cognitive and personal attributes that predict capability may be assessed through blended psychometric ability tests and self-report questionnaires. For high-stakes talent management decisions, psychometric data should be complemented with other sources of direct observation data such as past-performance evaluations, multi-rater surveys and business simulations. |

Character

|

Character is defined as the quality of judgement and decision-making of an individual, that is based on their personal traits, values and virtues. It is necessary to not only understand what an individual can do, but also how they conduct themselves when things are going well, and when the going gets tough. In other words, assessing an individual’s character gives organisations an insight into how someone engages with the world around them, what they reinforce, how they engage themselves and others in conversations and what they value and choose to act upon.

Character has been demonstrated as a powerful predictor of future potential (Gandz, Crossan, & Seijts, 2008) and consists of aggregate traits, values and virtues that guide and direct behaviour:

|

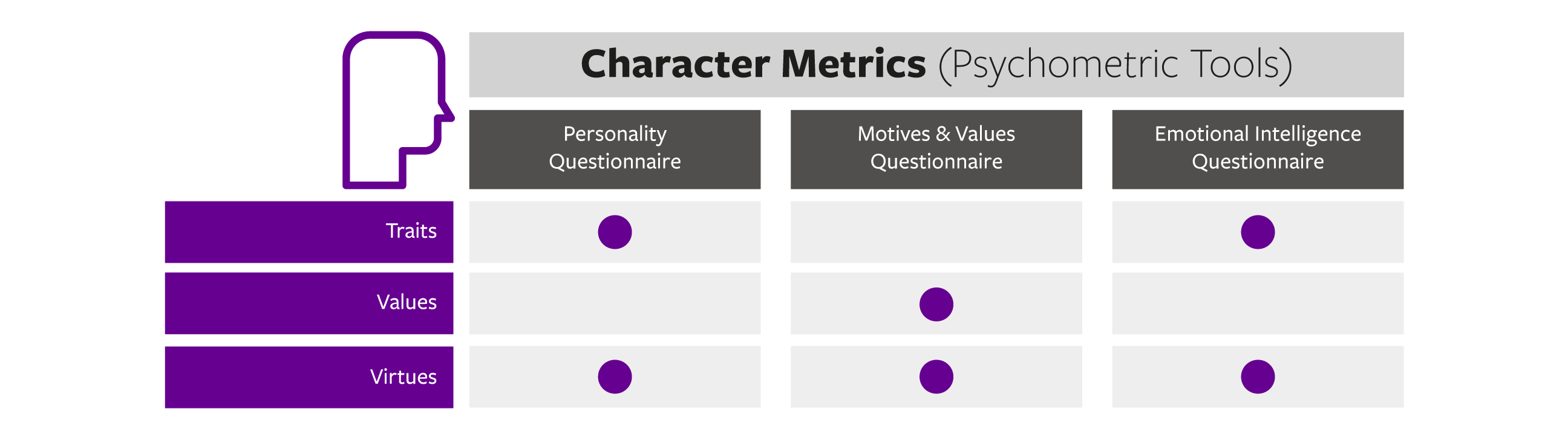

Assessing Character: Traits, values and virtues are most effectively and efficiently assessed using a hybrid blend of valid and reliable psychometrics designed to measure the constructs of personality, emotional intelligence, motivation and values. |

Commitment

|

Commitment relates to whether someone has the right drive, aspiration and engagement to act on their potential. Commitment is the specific driving force that drives an individual to keeping moving in their career progression and professional growth (Meyer, Becker & Vandenberghe, 2004).

Commitment is a key indicator of potential and used by over 90% of organisations as one predictor of high potential (Silzer & Church, 2009). Those who progress highest and quickest in leadership are marked by high career aspirations, specific career goals, and engagement to their career development and getting things done (Gerstner, Hazucha & Davies, 2012). The constructs of aspiration, engagement, and sacrifice have a significant effect on commitment to lead and performance potential, as described in research by Monzani and colleagues (2019). Commitment is defined as the intersection of the following three factors:

|

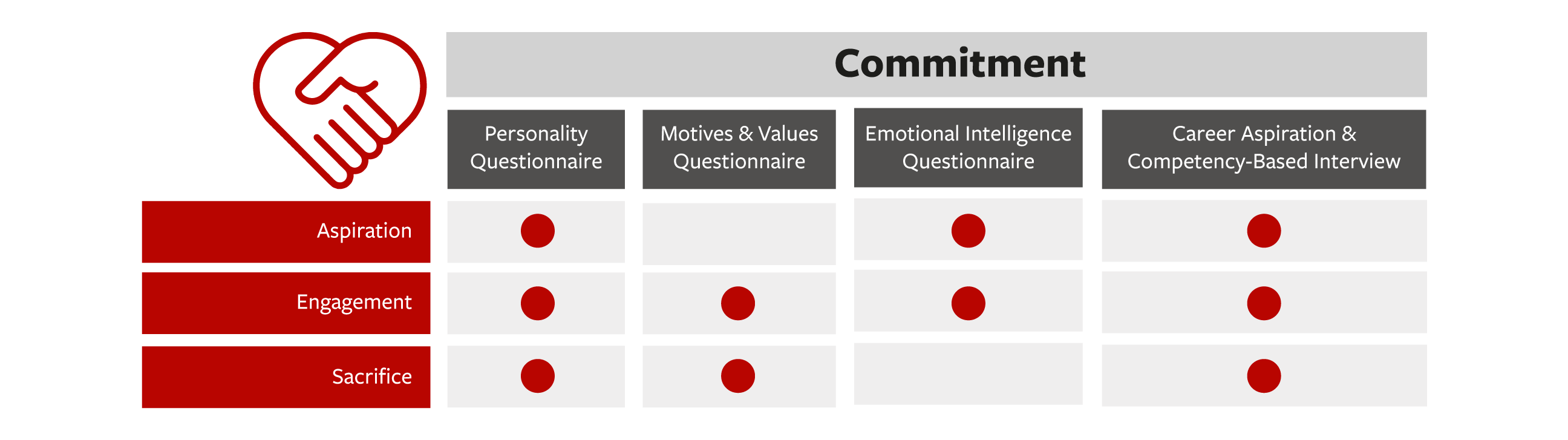

Assessing Commitment: Blended psychometric tools provide a rich insight into an individual’s likely commitment, drawing on elements of personality, emotional intelligence, motivation and values. For higher-risk talent decisions, psychometrics are best validated further through interview. |

Assessing & Identifying Potential

|

The assessment matrix below illustrates the recommended multi-method approach to assessing potential. For lower risk, volume talent identification programs, a purely online, psychometrically driven approach is suitable and allows for scalability and efficiency.

For effective Talent Segmentation (i.e. 9-box grids or talent heatmaps), psychometric data should be complemented with an in-depth competency or behavioural-event interview, alongside exploration of career aspiration and drivers and integration of reliable past-performance data. High-risk potential assessment scenarios, such as talent pipelining and succession planning, demand a more in-depth and robust approach including interviews, business simulations and other direct metrics of performance. |

Differentiated assessment methods may be used depending on the level of risk :

1. Talent Identification – psychometrically driven; best for identification of potential in larger populations (e.g. for selection into development or fast track programs) 2. Talent Segmentation – more robust validation with interview alongside psychometrics; best for creating Talent Grids in larger populations 3. Talent Pipelining – identifying potential for growth into a specific role or level; best for creating and validating succession plans |

References

|

Abraham, J., Renaud, S., & Saulquin, J. (2016). Relationships between organizational support, organizational commitment, and retention: Evidence from high-potential employees. Global Journal of Business Research, 10 (1)

Ahrens, A.H., & Cloutier, D (2019). Acting for good reasons: Integrating virtue theory and social cognitive theory. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 13 (4). Bartram, D. (2005). The Great Eight Competencies. A criterion-centric approach to validation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90. Boyatzis, R., Stubbs, E.C. and Taylor, S.N. (2002). Learning cognitive and emotional intelligence competencies through graduate management education. Academy of Management Learning and Education, 1 (2). Church, A. H., & Rotolo, C. T. (2013). How are top companies assessing their high-potentials and senior executives? A talent management benchmark study. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 65(3). Corporate Leadership Council. (2005a). Realizing the full potential of rising talent (Vol. I ). Washington, DC: Corporate Executive Board. Dries, N., Vantilborgh, T. & Pepermans, R. (2012). The role of learning agility and career variety in the identification and development of high potential employees. Personnel Review, vol. 41. Furnham, A. & Treglown, L. (2018). High potential personality and intelligence. Personality & Individual Differences, 128. Gandz, J., Crossman, M, & Seijts, G. (2008). Leadership on trial: A manifesto for leadership development. Ivey School of Business. |

Gerstner, C., Hazucha, J., & Davies, S. (2012). Motivators: What is important to leaders at different levels. In S.E. Davies (Chair), Understanding and supporting transitions up the leadership ladder. Symposium presented at the annual conference of the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology, San Diego, CA.

Martin & Schmidt (2010). How to keep your top talent. Harvard Business Review, 88 (5). Meyer, J.P., Becker, T.E., & Vandenberghe, C. (2004). Employee commitment and motivation: a conceptual analysis and integrative model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89,(6). Monzani, L., Becker, T. E., Crossan, M. M., Grabarski, M. K., Kalyal, H., & Saqib, Z. (2019). Inclusive organizations start with a leader’s commitment to lead. Academy of Management, 2019 (1). Parks-Leduc, L. & Guay, R. (2009). Personality, values and motivation. Personality & Individual Differences, 47 (7). Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Ready, D., Conger, J., & Hill, L. (2010). Are you high potential? Harvard Business Review, 88 (6). Schmidt, F. L. (2002). The role of general cognitive ability and job performance: why there cannot be a debate. Human Performance, 15. Silzer, R. & Church, A. H. (2009). The pearls and perils of identifying potential. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 2(4). |